Many readers will no doubt be taking the opportunity to explore Aldgate Square now that the barricades have finally come down and our pristine new public space is complete.

I’ve watched this project evolve over the last two years and I have to say the end result looks great.

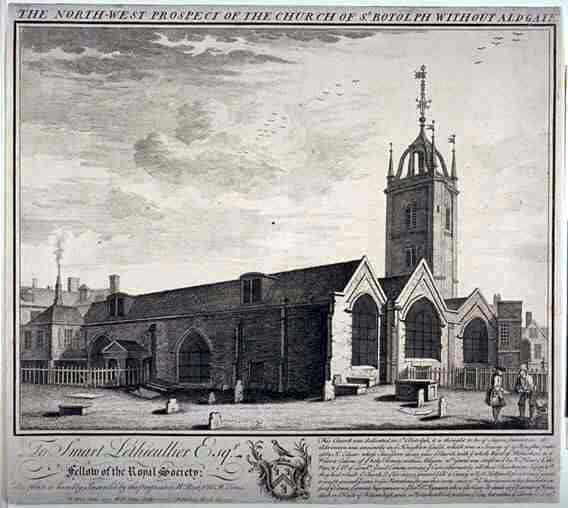

Personally, my favourite bit of the square is the significant expansion and redesign of the churchyard at St Botolph’s Without Aldgate. The new flowerbeds, hedges and compartmentalised little sections of garden are very easy on the eye. The grassy, northern part of the graveyard, once only really accessible from the back door of the church hall, is now easy for anyone to get to.

I’m actually sitting in the new churchyard gardens as I write this article on my laptop and I foresee this being a place that I will return to often. A group of kids who have just been picked up by their parents from Sir John Cass’ Primary School are having a great time rolling about on the new grassy area in the middle of the square.

The outside tables at Kahaila café are all full of people enjoying a coffee in the late afternoon sun and a group of men are huddled around an iPad in one of the nooks in the garden watching Russia play Saudi Arabia in the World Cup.

However, St Botolph’s churchyard and its environs were not always such a pleasant place for people to stop and mingle, and I thought it might be interesting to contrast today’s newly regenerated churchyard with the exact same spot from 180 years ago.

Like virtually all the burial grounds in the City of London, by the 19th century St Botolph’s churchyard was actually a pretty grim place. The problems centred on the fact that all the City’s cemeteries were simply overcharged with bodies.

In the days when everyone was laid to rest in the consecrated burial grounds of their local parish, there was a very finite amount of burial space that needed to accommodate an ever-increasing population of the newly dead.

Too much decaying organic matter crammed into too small a space resulted in the churchyards of the City being particularly notorious for the nasty, unwholesome stenches that emanated from them. All this greatly benefitted the coffers of the City’s parishes, which were in the fortunate position of holding a monopoly over a trade that provided an inexhaustible source of income. As one of the Square Mile’s largest and most populous parishes, St Botolph’s Without Aldgate was a prime example of a parish with an extremely overpopulated burial ground which was always struggling to find sufficient burial space.

The notion of having a permanent grave needs to be dispelled as a comparatively modern idea.In 19th-century London graves were allocated to their occupants only until space limitations required them to be reused again.

This could be within a shockingly short period of time, after which the mortal remains were then exhumed and interred either in charnel houses or ‘bone holes’ in the crypt of the church.

One particularly macabre event occurred on the morning of 7 September 1838, as reported in The Morning Post and other contemporaneous documents. Edward Cheeper, the Master of the local workhouse, was passing by St Botolph’s churchyard at 11am when he heard the piercing scream of a woman.

Alarmed, he hurried over to investigate and found the sobbing woman staring down into a deep, 20-foot grave. Sprawled out at the bottom was the apparently lifeless body of Thomas Oakes, the parish gravedigger. The great depth of this new grave was because it was intended as a multi-occupancy burial site for paupers and was designed to accommodate up to 18 bodies. The commotion rapidly drew a crowd of curious gawkers, and local fishmonger Edward Liddell volunteered to climb down a ladder into the grave in an attempt to rescue poor Oakes, although common consensus from the bystanders was that Oakes was definitely beyond help.

Eyewitness reports claim that as Liddell reached the floor of the grave and stooped down to put a rope around Oakes’ arms Liddell’s body suddenly wrenched “as if hit by a cannonball” and the hapless fishmonger keeled over and died immediately. In an act of considerable bravery, a third man then tried several times to climb down to retrieve the bodies of both Oakes and Liddell, but the air was so foul, putrid and revolting that he just couldn’t do it.

Ultimately, ropes on hooks had to be used to haul the unfortunate victims back up to the surface. At the subsequent inquest, it was decreed that both men had been fatally overcome by the noxious carbonic acid gas emitted from the thousands of decomposing corpses packed into the relatively tiny churchyard.

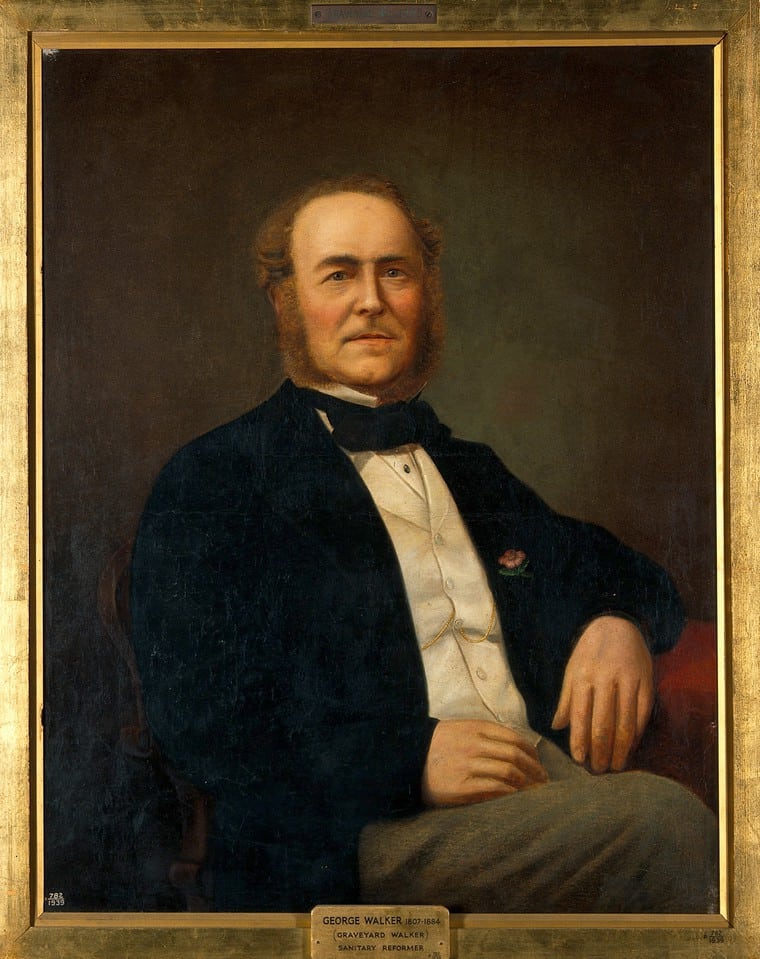

This rather morbid event was cited by Dr George Walker in a dossier of evidence he published in 1839 exposing the scandal of the disgusting, overcrowded and unsanitary state of the City’s burial grounds. Walker was a London GP and was extremely concerned at the health implications of the living and the dead being in such close proximity to each other.

Walker’s efforts eventually led to the passing of the Metropolitan Burial Act in 1852, which strictly prohibited any new burials in the churchyards of the City of London on the grounds that these were injurious to public health.

Instead, massive new out of town cemeteries were opened, such as the City of London Cemetery in Manor Park. Here, there was finally ample space to ensure that people could give their loved ones a dignified and permanent place where the dead could genuinely rest in peace.

Ian McPherson is a City of London Guide who lives on the Middlesex Street Estate with his partner and young daughter.

Ian McPherson is a City of London Guide who lives on the Middlesex Street Estate with his partner and young daughter.