FOR those unfamiliar with 20th-century American documentary photographer Dorothea Lange and her modern-day British contemporary Vanessa Winship, it isn’t immediately apparent why the Barbican Centre decided to present their work together.

The double-bill of Lange’s Politics of Seeing and Winship’s And Time Folds spans nine decades, two continents and countless societies in various states of decay.

Common themes of poverty, migration and identity unfold across the 18 rooms but it isn’t until the final two – Winship’s portraits of small-town America in the grips of the economic recession – that the two exhibitions are revealed natural bedfellows.

The critically-acclaimed series, She Dances on Jackson, shows young Americans in the grips of the economic recession; vulnerable, preoccupied with worry, and even a little defiant in their desolate settings. All seem to be asking, in their own way, ‘what happened to the American dream?’

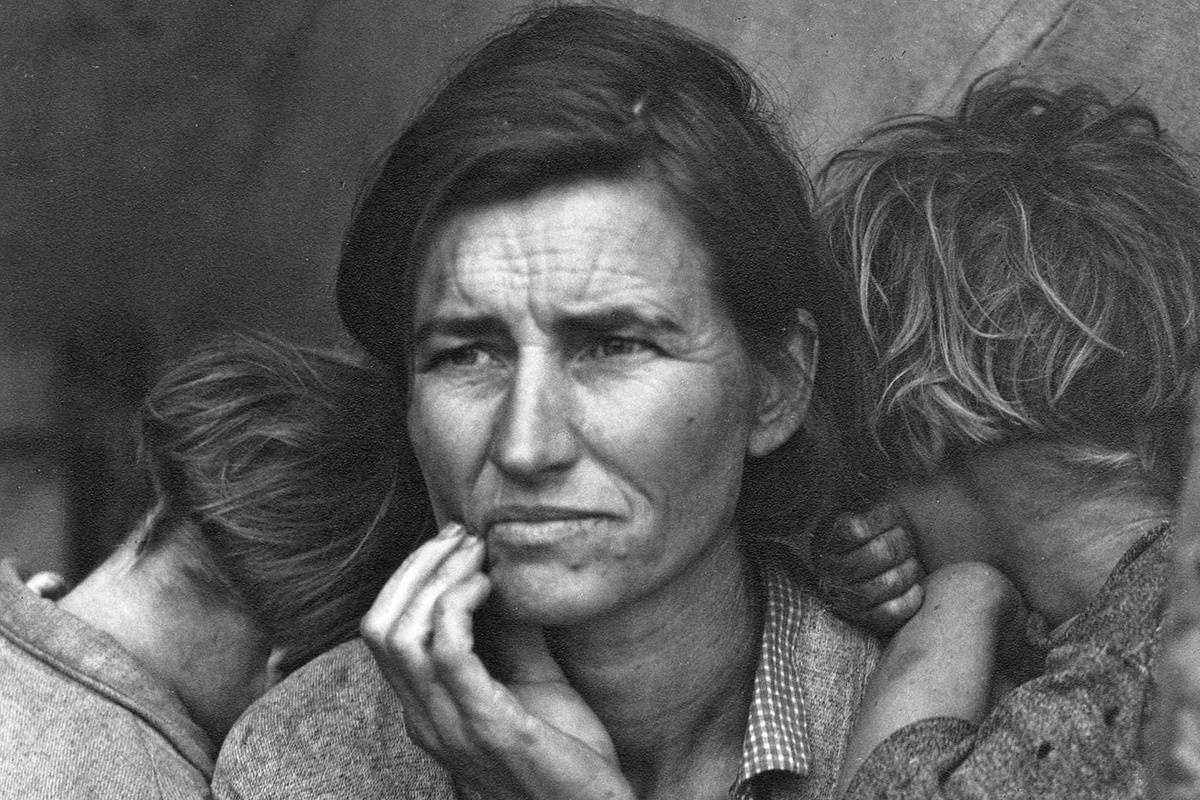

It’s the same question downstairs throughout Lange’s chronicle of the Great Depression in the early 1930s, posed by the urban homeless in San Francisco, the 300,000 refugee farmers of the Midwest dust bowl states, and, her most famous subject Migrant Mother.

There is an entire room dedicated to the portrait of Florence Owens Thompson and her children in a desperate community of pea pickers in Nipomo, California, which would become one of the defining images of the Great Depression.

In it, Lange ponders her work documenting the plight of the dispossessed for the Farm Security Administration (FSA), as well as her relationship with the subject: “She seemed to know that my pictures might help her, and so she helped me. There was a sort of equality about it.”

The sense of social purpose gets stronger moving into Lange’s period documenting the internment of more than 100,000 American citizens of Japanese descent following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour in 1941.

The War Relocation Authority, which commissioned the series, kept the photographs sealed in the National Archives, prompting open criticism from Lange who said: “They wanted a record, not a public record”.

After the war, Lange broadens her critical gaze to ponder the failings of the US justice system in Public Defender and the rise of consumerism and ownership at the cost of small-town life in The New California.

Winship’s work, by comparison, avoids specific sociopolitical contexts, instead taking a broader look at life on the margins of society.

Often there’s despair: dilemmas of identity, belonging and exile in the post-communist Balkans, lush landscapes marred by conflict in the Eastern European state of Georgia.

Sometimes there’s hope, as in the case of Sweet Nothings, a portrait series of schoolgirls from Turkey’s eastern borderlands that presents a society bound by memories of state-imposed control in the near identical uniforms, but making progress in the small details of individuality.

Ultimately, though, it’s uncertainty that unites these subjects and indeed those documented by Lange. A disquiet that reveals this pairing as a neat, if deeply troubling, package.